writing

STU MEAD SECONDS #45, 1997 – interviewed by Steven Cerio

STU MEAD

SECONDS #45, 1997 – interviewed by Steven Cerio

STU MEAD, master of the wiley prepubescent, slaps away at his slick, throbbing canvases deep in the Midwest – St. Paul, Minnesota, to be exact. Mead, luckily working in a community that prefers to turn a blind eye to what he does, has managed to build and sharpen one of them –there artistic visions ya read about in those fancy books. And he does it with a painting style so thick and creamy it takes a few minutes for the local grocery to dig through the sickly sweet camouflage to the tangy puerile center.

Mead dangerously acknowledges underage sexuality, and occasionally deflowers it – a forbidden act even in the wide-open world of art. But remember, the urge to depict is not an urge to act. There’s a definitive wall between the two, so just relax – it’s not newsreel footage, it’s not in your living room or your basement. It’s just in your head.

SECONDS: Is your work pornographic or erotic?

MEAD: When it’s sexual, I think it’s pornographic. “Erotic” is just a softer, more acceptable word. It symbolizes non-threatening pornography. With “pornography,” you picture something gross and matter-of-fact with no romance, no mood – just clinical pictures. Really, pornography is just a word covering explicit art and stories. I think the term was originally defined as “stories of, or by, harlots.” That’s all it originally was. “Pornography” is used to negatively attack people, but it’s a more benign word. I just like “erotica” because it’s so-

SECONDS: So Penthouse?

MEAD: Yeah, it’s generalized.

SECONDS: People tend to use the word “pornography” when they see women in degrading positions. You tend to glorify your women. It’s usually girls in power over the humbled man sneaking a quick glance.

MEAD: I think it reflects the sense of being inadequate next to this intense human being that’s making my body respond in these weird ways. When I depict a male, I’m depicting myself feeling like a schmuck next to this perfection. One enhances the other, just like strippers in old burlesque shows appeared beautiful because of the comics that performed along with them.

SECONDS: Is that a microcosm of male-female relationships?

MEAD: Maybe it’s a way of countering it. Obviously, with the patriarchal structure of society, men were the bosses. I’m sure there were very few households where the father wasn’t king, but for the entertainment he’d see himself as a helpless buffoon, the victim of feminine wiles.

SECONDS: Do your paintings display how you react to girls on the street?

MEAD: Oh yeah, I think so. The pictures are pretty much done without anyone in mind as an audience. When I do them, I strive towards forgetting who else would see them, so that I can pour myself into the picture. It’s always about me. Either I’m the male figure in the picture or it’s me voyeuring into a scene with females in it.

SECONDS: With Japanese Manga, five-year-old girls have the same body as thirty-year-old girls. What age group are you depicting?

MEAD: Women of all ages are beautiful and I merge them together when in what I depict. I think that’s typical of men who use imaginary females in their art as a fantasy vehicle. I hate to admit it, but that’s what I do. Girls can be power figures but a woman is darker. A women in my work is – I don’t know, what’s the world – “menacing.” I’m attracted to these pictures of girls because they’re shorter than me. I’m a short person so they’re somebody I could control. I’m thinking of a picture I did of a guy in a hospital room where there’s two nurses fondling each other and drinking gin. It’s the quintessential thing of being tormented by women, but pleasant tormenting. A lot of it is me reflecting the images I grew up with and have maintained throughout all my life, not having relationships with women –

SECONDS: Do any of your paintings start as masturbatory fantasies?

MEAD: I’d say a lot of them do. If you look at the work I did up to four years ago, you’d see a lot of sexuality in the work – but it wasn’t predominant. In the last four years, I’ve taken more work directly from my sketchbooks and that tends to be masturbatory images.

SECONDS: Are you a collector of pornography?

MEAD: Yes, I do have some. I’d hate to say “collection.” In my library, I have a bunch of pornographic artwork.

SECONDS: So you’re more into the artwork than the mass-produced magazines?

MEAD: Well, over the years I’ve bought a lot of magazines, that’s for sure. I have a love-hate relationship with them. I accumulate them but feel a disgust about having them.

SECONDS: But the art books don’t give you that feeling-

MEAD: No, they don’t, because art has a way of – it just doesn’t have a stigma. If Leg Show didn’t have this immediate stigma, I probably wouldn’t feel that way. The thing about handmade images is that they have so much to say about the artist.

SECONDS: How do women react to your work?

MEAD: Over the years, some of the strongest response I’ve gotten have been from women. Yet, my more recent work has alienated women – not that I’m trying to connect with them. (laughs) There’s plenty of grants here in Minnesota- it’s a good place for artists in that respect – and I’ve gotten a few grants over the years. I feel that because my recent work has been more pornographic, it’s been really hard for me to get through that grant process. On at least two occasions I knew of, women on these panels were completely disgusted.

SECONDS: How does the Mike Diana case apply to you? Do you feel any reverberations from that?

MEAD: No. That was a case where he was prosecuted in the courts. Minnesota hasn’t done anything to attack artists in that way. This state has a long Left Labor tradition that goes way back.

SECONDS: But don’t you think the attitudes that put him in jail exists in all cities?

MEAD: Sure. But here it’s a case of wanting to politely ignore offensive work and not dignify it with any kind of attack.

SECONDS: Has anyone had you do work to their own specs? For example, “I’d like three young girls undressed, standing on the hood of a Volkswagon.”

MEAD: I’ve never been any good at fulfilling other people’s visions. I don’t put my heart into it when it’s not my vision.

SECONDS: There tends to be a lot of defecation going on in you pieces. Is it fetishistic or representational for you?

MEAD: Both. For years, when I’d draw some orgy scene in a sketchbook, there’d always be someone shitting while getting screwed. Like I said, in recent years I’ve been culling more from these private drawings. I’ve painted pictures with this scatological subject matter and come to see that it’s connected self-degradation. I’ve done pool scenes where there’s all sorts of things going on – people swimming, people drying themselves off after getting out of the pool – and there’ll be some girl crapping into a bowl while some attendant is holding it in place for her. I’m just imagining these girls crapping on this paradigm of mine.

SECONDS: What about “Creative Children”? That to me, is a flagstone of your career. (Editor’s note: We cannot show this piece. Sorry.)

MEAD: There, I wasn’t trying to make a social comment, but I was trying to show these girls are the gods of their world and are producing men out of their own poop. It’s creating a myth.

SECONDS: Do you get feelings of guilt from doing this work?

MEAD: Oh yeah.

SECONDS: But you’ve said acting out any of those images is impossible for you.

MEAD: Yeah, it’s impossible for me for many reasons. Growing up disabled, I know what it’s like to have a rough time of it as a kid. For me to impose adult sexuality on a kid would be impossible to do. But I do think I am a pervert.

Cerio interviews ROBERT WILLIAMS Seconds #27, 1994

ROBERT WILLIAMS

Seconds #27, 1994 interviewed by Steven Cerio

From the sweat stained pits of Left Coast comes Robert Williams, a lone hot rod runnin’ on the swamp gas of popular culture. You’ve sucked up his drippings from the pages of Zap Comix. His paintings read like the diary of a teen speed freak raised on Wonder Bread and model airplane glue whose life is spent giving or oral favors to death in the backseat of a Hot Wheels car, with one hand full of titty and the other scraping the last speck of meth from the foil. Williams sends you barrling through a never ending hell of Freudian slips where nickel and dime whores writhe before you on marzipan hot dog buns while their bad tit jobs and chop-shop features shine like the prettiest Playboy dreams but reek like the towel hamper in a men’s gym.

Our cum-drunk savior of Rock& Roll iconography stirred up dick-envious feminists with his Appetite for Destruction, a painting leased by Guns N’ Roses for their debut release. After almost half century of sodomizing the art Establishment, ol’ Hieronymous Bob can still send seekers of arcane knowledge and their benny fueled woodies back to their holes – but, more impressively, he can always have them out.

SECONDS: Now that you’ve become an established entity, how do you feel about your fans and the crowds that come to your shows?

WILLIAMS: Well, I don’t know how established I really am. Blackballed in a lot of shows for one reason or another, a lot of people just don’t care for my work. You see me from a while different side. If you were in my shoes, you’d see me continually trying to get ahead and not getting anywhere. Go over to the Museum of Modern Art and try ot get in there and see how you feel. You feel like nobody’s at the door.

SECONDS: A lot of people see you as an icon of underground culture – you don’t fee like that?

WILLIAMS: I do. I feel hundreds of young artists behind me trying to figure out where I’m going so they can go there too – and there’s no place to go. There’s just no academic acceptance of us, it’s just in very small quarters. We had a show out her in ’93 called Custom Culture at the Laguna Beach Art Museum. It was very successful and it was made up primarily of underground artists. That was the first real big underground art show. That went to Baltimore and Seattle and was very well received. I think that was a real breakthrough. Then again, everyone involved with it was totally categorized as some kind of car nostalgia situation with Ed “Big Daddy” Roth. WE have to take the good with the bad.

SECONDS: Who are the Art Establishment and what do they want?

WILLIAMS: It’s made up of different factions and you have to examine each faction. Let me try to describe them: First you’ve got a giant amount of art students that aren’t very talented and they have to go with what they’re capable of doing. They’ll find heroes that aren’t very good, heroes that are abstract and minimalist, stuff that doesn’t require years of technical training. You’ve got that large amount of students that go to schools, and schools will teach these people what to know because these kids have money. So they’ll teach them this retarded formal art generation and the teachers in there are students who’ve been taught the same crap. You’ve got a recycling of students who have no other way to make up a living but to become teachers. On top of that, you’ve got a museum system that’s got to kowtow to this giant amount of art students and art schools. They have to mediate between what the public wants and what these students are capable of doing. What they do is promote material that goes along with an already established storyline of what art is. This is based on the social trends, what’s hot in New York right now AIDS, gay rights – you have to consider all these elements as what’s gong to make your art. The more the thing goes down the line of success in museums, the further it gets away from actually being able to draw, think and have an imagination. You’ve got a lot of performance artists that are throwing together stuff that deals with social issues and it’s heralded as great art. The third element that dominates the art world is the foundations that fund all this stuff. Foundations in reality are nothing more than tax write -off factors that think they’re doing a charitable thing with this excess money that the have to get a tax write-off on. So they start stabbing it into art and what the further do is underwrite blue chip artists because it’s the safest thing to do. They’ve ventured into younger experimental artists and invested really highly in the 80’s, millions of dollars, and this whole house of cards, the art schools, the art students, the museums, the foundations, the galleries, collapsed in 1987 with that collapse of the stock market. Prior to that you could just have a room with a two railroad ties chained together and paint it day-glo and call it “Composition #14” and get $25,000. The average art in the 80s was making millions of dollars. Everyone feared there was really no value for this crap, and when the collapse came, all these foundations and museums were left with warehouses full of shit they paid fortunes for. It wasn’t worth the fucking materials they were made of. Japan took it in the ass to the tune of a couple billion dollars on these wild investments. You’re in a period right now where there’s kind of an open window if you’re a good artist. If you’re capable of producing good oil painting you can always ell that somewhere even in the face of these hard times. It’s awful hard for academic artists everywhere.

SECONDS: Do you consider cartoons as Americana?

WILLIAMS: Because of the movie industry in the 20s and because of Thomas Nast after the Civil War, it is probably more dominant in the United States. Of course Europe’s always had a lot of good cartoonists. It’s just a thing that’s happening now and it’s happening all over. There’s a couple of bad effects of it. One bad effect is becoming a thing in itself on its own. It’s not trying to force its way into the art world, it’s trying to keep itself separate and be an art form itself. I think artists make a very critical mistake when they do that.

SECONDS: A lot of your work is a parody of White culture.

WILLIAMS: Coming from a middle-class family in the 40s and 50s, that’s my take on the world. There’s a certain sarcasm in what I do, so I’m very careful not to elaborate on other people’s cultures because it’s sure to be misinterpreted. I just stick to with the observations from my White Mans’ world.

SECONDS: What do your naked cuties represent?

WILLIAMS: The naked cuties is my appreciation of women. I’m fascinated and preoccupied with women and I know a lot of other people are too. One of the first things you do when you learn to draw is draw a naked lady. I know the very first thing that was done with a camera was to get some girl to take her clothes off. Pornography is one of the early uses of the camera. Of course I get into a lot of trouble with feminists and progressive liberals about my use of women. In my mind’s eye, I’m not hurting anybody.

SECONDS: Unlike your older work, the women in the newer paintings look like mannequins.

WILLIAMS: One natural thing is, when you draw women, you tend to draw stylized imagery. It’s been worked out by a large consensus of other artists. You tend to stick to those stereotypes unless you get a model.

SECONDS: Do you use reference?

WILLIAMS: I use references and sometimes I use models.

SECONDS: How did the Appetite for Destruction scandal affect you?

WILLIAMS: That blossomed off of Guns N’ Roses. They’ve sold fifteen million records that either had that on the cover or had it on the sleeve inside. There was a tremendous reaction to that by a number of feminist groups and church groups. The PMRC bitched and moaned about it but the loudest cry was from feminists in Northern California and they picketed those Tower Record stores. About six or seven women’s groups Northern California jumped on that and first they hit Santa Cruz and said they were going to picket all the record stores that had it. So all the stores pulled it off the shelves except for Tower Records and they stood up against them for three or four weeks. Then the same thing happened in Berkeley. Some woman came to my defense in Santa Cruz. These feminists found some private business about her and pulled some ugly fucking techniques. Tower Records never gave up and the feminist groups ended up switching from Guns N’ Roses to pornographic video games.

SECONDS: It must have been fun watching that happen.

WILLIAMS: It wasn’t fun for me because I had to defend this thing in the newspapers because Guns N’ Roses weren’t very articulate. I had to have some pretty sharp answers because I was on the firing line with these broads. It’s kind of nerve-wracking; there’s nothing fun about it. You don’t know if these women are going to file a class action suit against me. You don’t know what the fuck’s going to happen. It’s not a thing where you say, “Oh boy, I’m getting publicity.” You start thinking, “Am I not going to be able to draw women anymore? Are the bitches going to work on me to the point I can’t even represent their breasts?”

SECONDS: Could you imagine a type of music to go with your work?

WILLIAMS: I could see a lot of Punk Rock music. I could see a lot more polished music like the Chili Peppers, Butthole Surfers- music that’s got movement. Your ear listens because there’s going to be a change but at the same time there’s a driving beat that keeps your blood flowing.

SECONDS: Would your work change if you weren’t worried about sales and public sentiment?

WILLIAMS: The reason I haven’t gotten very far is because I do what I want. I never get big write-ups in big magazines because my stuff’s offensive to the vast majority of people.

SECONDS: Do you find it healthy to witness violence and depravity?

WILLIAMS: I don’t know how healthy it is and I don’t know how bad it is for you but I do know it’s a starving demand that everyone has. You take the most clean cut conservative self-righteous woman who goes to church and she’d just be happy to death to see a rapist beat to death. It’s in all of us. One thing we all have to distinguish between is our thoughts and the reality around us. We have to be able to think things that are wildly imaginative but not carry them out in reality.

SECONDS: What do you consider a weak point in your work?

WILLIAMS: I’ve got an awful lot of shortcomings in what I do. I look at my body of work and in reality, compared to a lot of artists in history. I’m kind of mediocre. But compared to artists today, I come off like Titian or somebody. I do have a lot of shortcomings but on the other hand, I got tenacity and I keep working. Unhappy as I am with it sometimes, I look at other people’s work and I get back home and I’m just tickled pink.

SECONDS: What’s a working day for you?

WILLIAMS: Between 1985 and 1992, I used to put in about ninety hours a week. I’d get up at 4:20 every morning. I produced a tremendous body or work. I worked seven days a week but that pooped out after a show in New York. I had thirty paintings in there and that just burnt me out. I’m still working pretty good now but I work eight to ten hours a day now instead of fifteen hours a day.

SECONDS: How fast do these things come out of you?

WILLIAMS: I produce a painting a month now. But I’m doing a lot more detail in the paintings. I reached a situation where there’s a large waiting list of buyers and I’m just trying to level out to a nice work place to keep going for a long time.

SECONDS: In Freudian terms, your work could be viewed as product of deep-rooted sexual problems. What’s your viewpoint?

WILLIAMS: One of the big influences on me, and especially on comic book artists, even if they don’t want to admit it, is the Surrealist movement of the 20’s and early 30’s. That had a tremendous effect on modern society, especially graphics. You don’t see that much in buildings, but it had a tremendous effect on cartoons, animation, abstract thought. Surrealism had an effect on everybody. One thing that was key to Surrealism was the use of the imagination and the deep search of the subconscious. A lot of experts now believe there isn’t really that much to the subconscious. I’m kind of inclined to agree with that. I have a goal to pursue a system, or attitude, or philosophy to figure out what makes up imagination and what are the powers of imagination and how to develop an abstract thought and synthesize pure imagination. I don’t think anyone has really sat down and tried to figure out what is imagination. What are the facets of imagination that have to deal with the manic notions of something being desirable? I just think there’s a new for imagination to go in. I’ve always been fascinated with looking into some kind of new mental stepping-stones into a depth that hasn’t been plundered yet. We’re all endowed with this gigantic amount of imagination. It’s so bothersome to people because it’s so Freudian, anal and sexual and they put it in the Bible. The Bible’s a good place if you have a lot of imagination. You could just go through the Bible and drain your imagination off into these four-thousand-year old stories. That’s primarily what the Bible is for, a place to put your hungry imagination. A lot of people aren’t that hungry for The Bible because they’ve got other places to put their imagination, like in the movies, in comic books, video games, all the other entertainments that weren’t available two hundred years ago. Right now we’re supposed to be in the most enlightened time in history, yet you’ve got more fucking idiots involved in astrology and occult and witchcraft and crap like that and they’re drawn in because of the romantic imagination involved.

SECONDS: Do you read a lot?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I read a lot. I’m very interested in history and taking situations that happened and trying to reinterpret them in another view that is not a popular view. It’s seeing things through my own eyes. Like taking someone out of history, reading everything about him and imagining if you knew this idiot. Napoleon would be a good example. He occupied a power vacuum when there was a need for a strong man. Things would just of his way because he was a lucky man. He wasn’t a brilliant son of a bitch, just strong like Hitler. If Hitler wasn’t born, Hermann Goering would have filled his spot. If Hermann Goering wasn’t there than another idiot would have filled his spot. You look Hitler and you see this poor retarded idiot who tried to be a house painter, tried to be an artist and had a real constipated imagination. He was a fairly good renderer – good dexterity and hand eye control – but he would not allow himself any luxury in imagination and he hated anyone who did have imagination. He did everything he could to persecute any of the modern artists. I guess I said enough about al that.

SECONDS: What’s your view of the New York art scene?

WILLIAMS: All these young artists try to live the romance of disparity. It’s kind of a pathetic scenario. You’ve got a large amount of artists that end up being role models for people that can’t do things. You have to give artists as much longitude as possible, you can’t stifle the arts. On the other hand you have this giant amount of people that cant’ do anything that are filling the art schools. There was a hundred and fifty thousand people on the island on Manhattan representing themselves as fine arts artists. Can you imagine that number of people? Have you got the scope of that? It’s unbelievably brutal. There’s nothing really wrong with it but you’ve got this giant work force that’s not working.

SECONDS: It’s to the point that they accept that their lives and their art are masturbation.

WILLIAMS: When I was young, they didn’t come to that reality, they still had all this fucking hope and it was even worse then. When I was an art student in ’63 and you’re in a class of forty people, two of those people had a chance of making a living in the arts and they’d probably be teachers. Now when you’re in an art class of forty people, you’ve got maybe eight people that can make it. So things have quadrupled. You have this giant amount of success in thirty years but you’re still looking at thirty-two people that are sucking wind. They’re sure as fuck not going to like what I do because what I do requires at least a decade of training and artists are not going to take on a decade of training in this modern age because everyone wants to hand loose because some opportunity might come their way. They don’t want to bog down and learn how to draw, how to do landscapes or nothing like that, they want to be ready for that computer job that comes up, they want to be free to become a performance artist. They have to be loose and ready to go so they never learn a fucking thing.

SECONDS: How will computer animation affect the art world?

WILLIAMS: Yes I do. I think there’s more opportunities in art now than there’s ever been before. But you have to be capable and dedicated. You have to develop a rich imagination. Because museums are starting to have these collectors try to dump art on them so they can get a tax write-off. This stuff isn’t worth the fucking stuff it’s made out of. These big artists that were big in the 80s, if they’re lucky, they’ll get a third of what they were asking in the 80s. So the art world has come down to reality. People are looking for something solid and interesting to put their money in. People have not given up on the arts. I hear people say all the time in the galleries, “ People aren’t buying anymore.” Well, what the fuck is there to buy? If I gave you a half million dollars, what the fuck would you buy? I sure as fuck wouldn’t invest money in that crap. I’d buy German helmets or hot rods or I’d buy fine old artwork. The market on good old Renaissance artwork hasn’t dropped at all.

SECONDS: Your work moves faster than MTV.

WILLIAMS: When I put a painting together – remember, a painting is a static two-dimensional thing. People already know that when you represent three dimensions it isn’t really three dimensions it isn’t’ really three dimensions. They were on to that trick five hundred years ago. So when you have a painting, that Renaissance style of entertainment has got to compete with video games, good modern pornography, sports, television, radio, so you’ve got to have energetic visual devices in the painting to lock people in there. Part of locking people in is coming up with imagery they don’t necessarily like but will hold them. Of course this requires gratuitous sex and violence, use of children in unpopular ways, things like that hold to people. If you can hold a person on one of your paintings for forty-five seconds, there’s a good chance he’ll look at another one of your paintings. If you can get him to look at three or four paintings, you’ve got the guy by the nuts. He’ll remember you, he’ll hunt up more of your work, he’ll talk about you to people that will buy your books, buy your prints and encourage people with money to buy the paintings. So you’ve got to come up with interesting devices – the use of color, graphics, contrast – you’ve got to use every fucking thing in your arsenal to get attention and hold people.

Cerio interviews Joe Coleman “A CAVEMAN IN A SPACESUIT” Seconds #50, 1999

Joe Coleman “A CAVEMAN IN A SPACESUIT” Seconds #50, 1999

interviewed by Steven Cerio

JOE COLEMAN is one of the most recognized cult figures in American Art. He covers paintings with microscopic detail in order to lovingly skewer the mind and eye – but his paintings aren’t about paint: they’re graphic expressions of memory and intelligence. Coleman records his own inner knowledge like a Speed-crazed librarian in a mindset where “absorb!” is the command of the moment. He is part of a tradition which traces back to Bosch, Breughel, Durer and Albright.

SECONDS: What’s more visually powerful, sex or death?

COLEMAN: Death as an image is somehow more powerful. We get to experience sex – and even before you actually experience sex it might be even more compelling – but at the point of actually experiencing death, it’s too late to have it as a memory. So it’s like looking at something that you’ll have to eventually experience, which makes it even more of a mystery. Sex may have mysterious elements around it but it’s something adults engage in all the time. So even though they might be aroused by certain images, it’s still familiar.

SECONDS: Are the things that thrill people as adults the same as what thrilled them as children?

COLEMAN: For me that’s true. It hasn’t changed that much, although it’s become refined. You need a stronger thrill, but it’s in a similar direction. The same way with drugs, where you need a stronger hit to get off. You just keep upping the ante, to have a more intense thrill.

SECONDS: I know what you’re saying. I don’t feel I’ve changed at all since I was a kid. I still have the image of what art should be –

COLEMAN: Oh yeah, the drawings I did in childhood are not really that much different. The subject matter is very similar. I still have these drawings of somebody set on fire, another person beings stabbed, and Jesus being nailed to the cross. All these images are still a major part of my work – even though the work itself had become more refined, the inspirations are still almost exactly the same as they were when I was a child, even though I know more about how to get more in touch in those images and how to find out how they relate to history, how they relate to me, and how they can be conquered in the sense of conquering fears or overwhelming forces. In the same way, to capture an image of death and to project it in some way like a shaman’s sacred object – like if you own a photo of death, even though people don’t usually think about it literally, it kind of makes you feel like you have some power over it.

SECONDS: Why do people equate violence, death and pestilence with maturity, while perceiving happiness and bliss as immature qualities?

COLEMAN: There’s something about childhood that’s looked at as being innocent. But if you really look at children, they’re full of all kinds of cruelties – and they have sexual desires as well. But adults tend to look at children in the manner of Adam and Eve in the Garden Of Eden. Maturity, which is usually linked to sexual maturity, is like the expulsion from The Garden of Eden. And from then on, you’re living this kind of corrupted adulthood full of evil, which you don’t see in childhood. A child could do something really cruel to another child, and it’s not really considered evil because they’re still in paradise. But once they get old enough and do the same exact thing, all of a sudden they’re evil. It may have something to do with sexual maturity – somehow that corrupts the flesh. Remember, the tree Adam and Eve ate that contained the fruit of knowledge.

SECONDS: The whole concept of good and evil is sort of odd.

COLEMAN: Yeah, the concept of good and evil was formulated in order for civilization to work because you have to buy into this idea in order to live in a man-made environment. This was manmade rules; not nature’s rules because nature doesn’t really care, nature has no sense of good and evil.

SECONDS: You die and you go back into the ground and break down so nature can grow more plants.

COLEMAN: Yeah, and we do kind of the same thing with animals as we do with kids. We look at kids and animals, and they may do really horrible stuff but we look at them as being innocent. But we look at ourselves as being imperfect and having fallen from grace. I think we fell from grace when we created civilization – that’s when primordial sex became a big sin. We’ve reached this point in civilization where we can’t be the innocent animal that can slay another animal without it being evil. It’s pure, but we’ve lost that by becoming civilized.

SECONDS: I’m guessing from your work that you prefer to witness anguish over bliss.

COLEMAN: I don’t’ know if that holds true personally, but the work deals with more anguish than bliss, certainly. But I’m not sure that it’s more important for me to try and paint that stuff. What’s the point of painting a beautiful sunset? It works; there’s no need to transform it into anything. But when I paint really disturbing things, there’s some need to control it or define it or isolate it – to put charms around it to protect me from it. You don’t need to do those things to something beautiful necessarily, except the way I paint me and my girlfriend – which is trying to protect love and trying to prevent it from escaping. But that painting of bliss is connected to fear as well because then you can hold it when you’re afraid of losing it.

SECONDS: So you’re trying not to keep anything, you’re trying to exorcise it. Do you consider yourself enlightening by frightening or frightening by enlightening?

COLEMAN: It may be enlightening, but the only one I’m trying to enlighten is me. I can’t pretend to enlighten the world. It’s nice if that happens, but what’s really exciting for me is the engagement with my own enlightenment, for me to learn things through painting.

SECONDS: Most artists don’t like to admit that sort of thing. That’s where the real outsider art comes from, doesn’t it?

COLEMAN: Well, I think so. When it’s real – not when people are calling it that, but when it’s truly that. The whole term “outsider” I think is very condescending and it’s used to create a commodity, which really takes away from the purity of it. You’re giving it this term to sell it with, which is very contradictory and it corrupts it. The funny thing about outsider art is that twenty years ago you had artists who’d gone to the best universities in the country and when they opened their mouths everyone thought they were great artists because no one knew what the hell they were saying. Now you’ve got these people who’ve gone to the worst prisons and madhouses and when they open their mouths no one knew what the hell they’re saying either – and they think that makes a great artist. But really, neither are great artists. In the end, it’s the work that’ s really important. There’s nothing wrong with having mystery, but there’s also a lot to be said for something you could truly understand and feel compelled by when you see it.

SECONDS: Does the artist’s identity at some point become more important than the art?

COLEMAN: Yeah, certainly, that’s happening all the time with most modern art and it seems to be happening a lot in outsider art. These persons are judged by their life and not the art itself. It’s kind of like the huckster selling some real horrible life experiences – selling work that’s merited only by the person who’s paying. That should all be part of it but it should be intrinsically linked. The work has to stand up by itself, no matter what.

SECONDS: Do you have any problem with artists taking themselves very seriously?

COLEMAN: No. An artist taking themselves seriously is not a bad thing; that’s a good thing about the outsiders – they’re very earnest. That’s a good thing because there’s too many people being ironic.

SECONDS: Irony seems to be a staple of modern art.

COLEMAN: It’s very superficial. It’s just playing on the surface, acting very above it all; it’s not really getting in there. Once you jump down into the snakepit and you get your hands dirty, that’s when you really have something to offer.

SECONDS: Has the subculture been good to you?

COLEMAN: Sometimes it’s hard for me to thin there even is a subculture these days, it’s so subjective and so co-opted by the mainstream. I mean, Ed Wood was a major Hollywood movie – no one would’ve imagined that would’ve happened twenty years ago. That’s not to put down the movie because I thought it was great, but it’s just a strange time that we live in.

SECONDS: Yeah – it all got sucked up, starting with the music. Underground heroes became the mainstream successes. There used to be this quaintness – you do not want to share your underground heroes.

COLEMAN: Yeah, and it’s becoming harder all the time for that because the underground is disappearing – it’s constantly being sold to a big market. I don’t think there was a big market for so-called counterculture – but now there is, and it happened really fast.

SECONDS: What are your perceptions on mainstream Pop Culture?

COLEMAN: I don’t think I ever really got it, but I have personal interests. But I’m never gonna run out of things I enjoy – I collect old books and old movies and objects. None of that has changed over the years, and there’s never enough out there. As far as Pop Culture, I’m not really even sure what it is. Unless something’s put right to my face, I don’t see it. It’s just not something that’s important to me.

SECONDS: Your work has this insane librarian aspect with a sense of education about it.

COLEMAN: You’re probably right. I always collected history books and old religious art, too. My work is storytelling. Even though there’s a single image, there’s a whole novel with each painting, and every little image has a significance to it – nothing’s arbitrary. It does educate, I’m sure, but I was thinking more of being a storyteller rather than an educator. My grandfather was an ex-prizefighter that ran speakeasies in the Catskill Mountains during Prohibition, and I used to love hearing him tell stories. I’m not an educator in that I’m not trying to tell what people what to think. This is what interests me, and this is what I need to find out for myself – and I can’t tell you what you need to find out about.

SECONDS: The obsessive quality of your work reminds me of Adolf Wolfli –

COLEMAN: There’s a certain personality like that, and people who are not like that don’t understand it all. Some people have a problem looking at my work because there’s too much going on, while other people are the opposite – they need all the simulation. White rooms scar me – my place is crammed with tons and tons of stuff, and that’s how I feel comfortable. I have one room that’s a shrine, it looks halfway between a dime museum and a church, and my work room has every corner of the walls pasted with newspaper clippings, photos, posters, decals, nailed to or taped to every square inch of the walls.

SECONDS: Are your portraits done with empathy or envy – or both?

COLEMAN: It’s more like method acting, where you become that person and you find those things in the character which are like you. In that way, they’re self-portraits. It also comes out of dreams of my home, especially where I grew up, across the street from a cemetery, which very much became a part of my work, stylistically as well. I spent a lot of time playing in the graveyard and studying the headstones – the lettering in my work dates back to that period of my life.

SECONDS: Type styles seem to really interest you.

COLEMAN: Yeah, because that’s something I’m really engaged with – I’m engaged with color, texture, lighting; and words have a similar level of visual engagement. For me, words are another part of creating this dense surface I’m after. I see words as very electric and vibrating – they have a sonic quality. To me, that’s part of the way of creating a sense of experience. In my experience right now, I’m talking to you and I have all these visuals going on. There’s visuals forming form the words I’m talking, and for the words that are also going on in my head. All these things put together are part of a total experience.

SECONDS: Aldous Huxley said people take words at face value; when you describe sensations like vertigo or angst or anger or tiredness, you can’t fully explain them.

COLEMAN: Yeah, sometimes it takes art to describe it.

SECONDS: If you had mainstream America’s attention for one minute and you could expose them to anything, what would it be?

COLEMAN: In terms of mainstream or not, it wouldn’t be one of my concerns. I share the things that I have an interest in. It’s more about sharing these experiences with people in general that share things that are of interest to me. I don’t think of what to say to people because they’re mainstream or counterculture; it doesn’t matter to me. What matters is what I’m feeling at a specific time – what I’m excited about. Where it comes from, I’m not interested. If they’re willing to listen, that’s a start. But if I find out that I’m talking to someone who really can’t understand, then I give up and go to somebody else.

SECONDS: One has to serve one’s self – some people would see that as selfishness.

COLEMAN: But the self is all you’ve got. It’s foolish to try and to claim you’re not selfish – it’s impossible to survive if you’re not selfish. The idea of trading is selfish but both parties get something out of it. It’s mutually beneficial. The point is, “What’s in it for me?” – which is honest and direct. I’m more mistrustful of the person who says he’s doing something for me than the person who says he’s doing something for himself.

Cerio interviews artist MIKE DIANA

Mike Diana

Seconds #38, 1996 – interviewed by Steven Cerio

Mike Diana is not only an artist, he is also an honorary enemy of the state. In 1994 Mike was indicted on three counts of obscenity for publishing, advertising, and distributing Boiled Angel, a comics compendium that disturbed the pious inhabitants of his small Floridian town Largo. Awakened from their splendorous slumber by word of a young, long haired trailer park child led astray by the wiley temptations of Satan, those inhabitants set out to protect themselves and future generations from Diana’s morally questionable narrative. So frightened were they of his sordid tales of child and drug use that Mike was convicted and ordered by the courts of Pinellas County not to approach within ten feet of any child under eighteen of age. He was sentenced to perform 3,000 hours of community service and was ordered to keep within the County confines for three years. In the frenzy to assign fault to Mr. Diana, he was even questioned for the Gainesville student murders while in custody. His home became open territory for the police to rummage through for anything they deemed obscene. Sheriff’s could’ve even run Mike in for cohabitating with stripper Suzi Morbid. The par met in the hall of the Pinellas County courthouse, each of them on their way to their own obscenity hearings.

“The judge gave the probation office and police permission to conduct warrantless searches of my apartment for any signs of me creating artwork that might be considered obscene.”

SECONDS: Did you set out to be the world’s most violent cartoonist?

DIANA: Yes.

SECONDS: Florida hasn’t been the best place for a blossoming artist like yourself. Would any of that’ve happened if you lived anywhere else?

DIANA: Probably not. They’ve been after me for awhile and I think they saw this as a way to get to me.

SECONDS: Couldn’t they come into your home at any time they wanted to look for anything they deemed obscene?

DIANA: Yeah. They judge gave the probation office and police permission to conduct warantless searches of my apartment for any signs of me creating artwork that might be considered obscene.

SECONDS: Would that include pornography if you had an issue of Penthouse lying around?

DIANA: I asked my lawyer and he said just to be safe I should get everything out of the house that might be questionable. I had those probation requirements hanging over me for about three months until the Comic Book Defense Fund paid the bond to get me off probation. They never did check the house but I was worried the police were gonna raid it.

SECONDS: In the news reports of your case, the funniest thing was that they had a logo for you, like they do for a tornado. What did it say, “Case Of The Boiled Angel”?

DIANA: Yeah

SECONDS: At the time it was stressful, but were you also laughing?

DIANA: Yeah, I was. I’d get up at eight o’clock in the morning to court and I’d be in court for four hours. They had protesters out there and religious people that’d show up and tell me I had to find the Lord. I usually didn’t get much sleep the night before. After I’d been in court all day, the news was the thing to top everything off for the night.

SECONDS: Did your parents follow the case?

DIANA: They watched it but they didn’t like the way the news reports brought up the fact that I was a suspect in the Gainesville student murders.

SECONDS: Is your case over now?

DIANA: The jury trial and all that is over. Since the appeal, it’s in the hands of the court and they lawyers. I don’t think I have to appear in court again except maybe on violation of my probation charges because I didn’t pay my fines. I was ordered to pay a $3000 fine at $100 a month and I owe them $200.

SECONDS: You had community service, right?

DIANA: Yeah, and the psychiatrist bill was $1200, so I owe that psychiatrist money.

SECONDS: What good has come from all this?

DIANA: Sometimes people don’t wanna print the stuff but all the publicity helped to get my stuff published, like my drawings about the case itself.

SECONDS: Have you had any trouble with publishers over content?

DIANA: Not really. Brutarian magazine didn’t wanna print the “Pisshole” comic. They’d been printing everything I sent and this one time they said they didn’t want it.

SECONDS: Did you have some trouble with Fantagraphics when some artists refused to be published with you?

DIANA: Yeah, that was Zero Zero magazine. I heard some of the artists and readers of the magazine thought my work didn’t deserve to be in the magazine with other artists.

SECONDS: When people talk about your work, they can’t decide whether or not you’re going for shock value. Do you have any intentions when you sit down to write?

DIANA: I want people to think about what is really going on in the story. A rape in real life is violent and I draw that out that way if I have a rape scene. Some people are just scared because they’re not used to seeing that stuff in regular comic form. It’s shocking that these things happen but I wanna make people more aware these things were going on around them, like priests molesting children. With Boiled Angel, the jury didn’t like the anti-religious things. The whole idea behind those anti-religious things is to be political. That should have helped me in my trial because if something has political value, it’s not supposed to be ruled as being obscene. The jury didn’t understand that, though.

SECONDS: I always sensed a deep sadness in your comics.

DIANA: Yeah. In Florida, they assume I’m trying to turn people into deviants, like these are comics that child molesters and pedophiles are gonna read, but I think it’s just the opposite. Those type of people aren’t gonna get into what I’m drawing.

SECONDS: How was school for you? It seems you’re always writing about traumatized middle school children.

DIANA: I didn’t like my middle school days. I was born in New York and moved to Florida when I was in the fourth grade. I never made a good adjustment in school. I was doing real good in school when I was in New York but I cane to Florida and we had a new living situation and I didn’t do as well in school as I used to. I know how much work I had to do to barely get by and pass to the next grade and that’s what I’d do. I was glad to finally graduate and get out.

SECONDS: Didn’t your mother treat you when she was training to be a nurse?

DIANA: When I as little, every time I was a little sick, I’d take medicine and get an enema.

SECONDS: She’d practice on you?

DIANA: Yeah.

SECONDS: Another things that’s prevalent in what you do is drug abuse. Where do you stand on drugs?

DIANA: I don’t use drugs myself.

SECONDS: Not even the light stuff?

DIANA: Every now and then – I quit drinking because of my stomach. It’s slowly getting better but it takes a while to heal.

SECONDS: You’ve messed around with light psychedelics, right? I see that in your work.

DIANA: I was never high at any time when I did my art. I’m usually sober when I draw, but it was an influence on my older drawings. A lot of the characters I was drawing fit in with the drug abuse.

SECONDS: Where do you pull your imagery from?

DIANA: Some of them are from nightmares I’ve had. Especially when I was young, I’d have nightmares every night. I always had this nightmare I was falling out of an airplane. But a lot of ideas come from dreams, and others from news reports. Like the “Baby Fuck Dog Food” story – the thing that gave me that idea was a true case in New York City. This stepfather killed his infant son and to get rid of the baby’s body, he fed it to the family dog, so they had to dissect the dog to get the baby out. Another idea I got from the alligators that are in the ponds here. There’s so many of them around in Florida now. There was one of these old persons’ mobile home communities and a lot of them have their own retention ponds with fountains. This little girl was visiting her grandma and playing by the lake and an alligator came up and ate her. As soon as something like that happens, they get rid of all the gators in the area. They kill them or catch them and put them in gator farms – there’s a lot of gator farms in Florida.

SECONDS: I’ve seen them sell gator skulls, too.

DIANA: Yeah, souvenir heads and skulls. They used to make ashtrays out of baby alligators. I saw an alligator lamp once where the alligator was standing up and the cord was going through it with a bulb and lampshade on it. I got this stuffed baby alligator with a prison uniform on. They used to have alligators dressed up like cheerleaders.

SECONDS: How much did they go for?

DIANA: Oh, like thirty dollars. In the Seventies, they’d sell baby alligators as pets. It wasn’t a serious pet; it was a fad.

SECONDS: Is it true about them resurfacing in sewers?

DIANA: Yeah, it is. It’s probably exaggerated, but I’ve heard of real cases.

SECONDS: Aside from being jailed, what’s the most negative reaction anyone’s had to your stuff?

DIANA: I’ve heard Dennis Warden, the cartoonist, hates my stuff.

SECONDS: What’s the worst?

DIANA: Well, when I was in Screw in New York somebody wrote me a postcard that said something like, “You’re a little no-talented punk and you should get a real life.” A lot of religious people come up to me and tell me I’m serving Satan.

SECONDS: Are people scared of you?

DIANA: My art is a lot different from who I really am and the way I act.

SECONDS: Isn’t that usually the way?

DIANA: Yeah.

SECONDS: Are you still using Flair pens?

DIANA: No, I’m using these technical pens and brushes. I’ve been doing a lot of acrylic paintings lately.

SECONDS: What’s the bare necessity for you besides supplies?

DIANA: Just any kind of an idea.

SECONDS: Do you derive inspiration from living in Florida, working in your father’s pizza shop or when you worked in his liquor store?

DIANA: Yeah, I always got plenty of good ideas working in the liquor store and pizza shop here. I used to draw wherever I was. When I was working for the school board, I’d get done with my work on the night shift and sit at a desk and draw a comic.

SECONDS: So, you work full time for your father at his pizza shop?

DIANA: Yup, making pizzas and lots of dough, but not a lot of money. That’s a joke I tell drunks when they come in. Church groups come to buy giant pizzas and I put a giant pepperoni cross on the pizzas.

SECONDS: Isn’t your Dad a slumlord?

DIANA: He used to be when he owned some of the trashiest apartments in Largo. They’d always write articles in the paper about him, like when he wouldn’t mow the grass. He got in an argument one time because the city said, “You’ve got to mow that property. The grass is too high.” They’ll come out with special rulers to see how hight the grass is and they’ll fine you. He just ignored all the letters and calls. When I started to be on the news, I said, “Remember when you were in the paper, Dad?” He used to have his won real estate business and it was called Buy Me Real Estate. On the signs he had a picture of his face with a big curly mustache. That was his trademark, a big mustache with wax. When he started turning into a slumlord, he got out of his own real estate and just started getting properties. The worst White Trash in Largo stayed at his properties. I always lived in his places.

SECONDS: Your dad must like your comics.

DIANA: No, he says they make him depressed.

SECONDS: Tell me some of the animal stories.

DIANA: In one of our houses, we had little tree frogs living in the shower. Little possums would walk through the house. My dad had a pile of garbage next to his bed and mice and rats were living in the pile. Before he went to bed at night, he’d set a mouse trap and catch a mouse right next to his bed every other night. He made the trap out of a piece of an aluminum lounge chair, a big board, and copper wire built into a spring. He also built a life size guillotine once that you could stick your head in. It had this big piece of sheet metal as a blade.

SECONDS: Did he use that to catch rodents?

DIANA: No, it was just to have in the backyard. It was an interesting place we were living – that’s the place we ended up getting kicked out of by the police. It was right after I got charged and the police were harassing us really bad. They sent a fire chief to look at our house and he declared it a fire hazard. Most of the houses in that are could’ve been declared fire hazards if they wanted to fuck with people, but they wanted to get rid of me so they condemned the house and gave us a week to move. We moved out and they bulldozed the whole house over. So we moved out of Largo. I’m living in Seminole now; that’s where the pizza shop is.

Interviewed by THE POUGHKEEPSIE JOURNAL

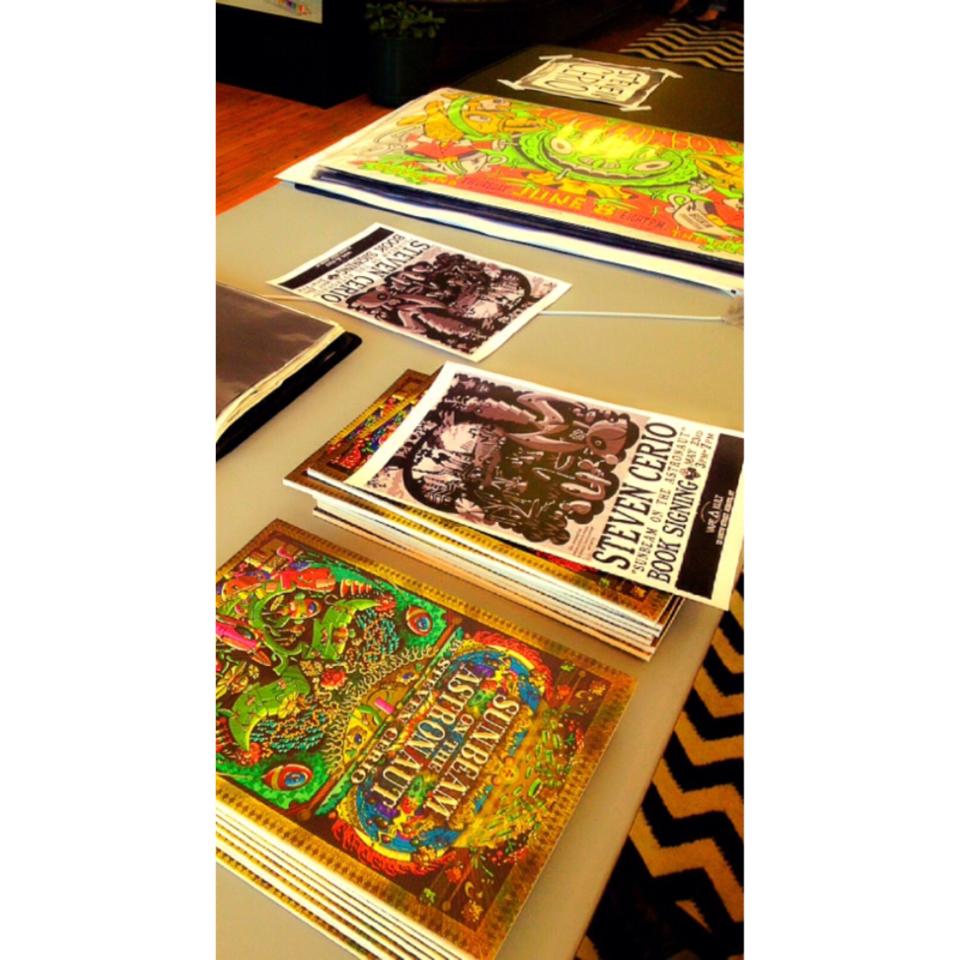

“STEVEN CERIO” interviewed by Jen for THE POUGHKEEPSIE JOURNAL

1 What meaning do you hope people find in your work?

Meaning is a trap. You can only become enlightened by your own phenomena. I’m not a symbolist. I’m not concerned with communicating a specific thought or personal insight; I try to convey energy. I see my work like everyone else does. It confuses me in the same way it confuses the viewer when I do it correctly. What interests me about life and art isn’t systems or exacting communication, that’s someone else’s job. I’m interested in the freedom it finds for itself, its synchronicities, magical coincidences and strange overlapping of events. The more traveling I do, the more talking I do, the more drawings I do, the more ground I walk over the happier I am. That’s why I’m here to do. That’s what my work means.

2. Your drawings and illustrations have an intrinsically childlike sense of play. How have you developed this?

Increasingly since I began drawing seriously in my teens, the ideas I was dealing with revolved around glee and a preternatural harmony expressed in my art to this day. In 1998 Juxtapoz magazine described my efforts as an artist as techniques to “synthesize joy.” I have in fact always been fascinated at how images depicting joy and happiness are located almost entirely on products aimed at child consumers. I wanted to engage with this activity, while providing it to a larger demographic. I believe that our adult society is pleased with its irony, sardonic wit and grim prophecy which it presents as intellectual property while continuously overlooking “childish” joy and pleasures: the sensations that each child and adult crave in perpetuity. To Quote George Petros from his introduction to my article in Seconds Magazine “it sometimes seems a shame that his innocent abandon is wasted on sour, seen-it-all adult audience.” To the contrary, I’ve taken a strange pleasure in adults finding the dark irony and violence they crave so strongly in my work when it wasn’t drawn there. It reinforces my assessment of this behavior that repulses me so.

I have always chosen animals and personified objects to express the emotion and intelligence in my work whenever possible. A smile on a flower shows a happy flower, a smiling man carries with him the history and behavior of his species, which is a lot of extra baggage I don’t care to lug around in my art.

2. What inspires you?

I play music in continuity while I’m awake. I like long, eventful, dense but meditative pieces. Captain Beefheart, The Residents, Can, John Coltrane, Soft Machine and Henry Cow all excel at that. I get a lot of pleasure from my collection postcards of bridges, freeze frame photographs of splashing water, time lapse films, antique squeaky toys, and cereal boxes as well. When I need to recharge nothing does it better than a couple of weeks hiking and driving in Arizona. I mail myself home boxes of cacti, beautiful stones and any toy totem pole I can get my hands on. In two weeks I can usually shoot at least four to five thousand photos. South Western Arizona is the strangest and most beautiful experience you can get without traveling space or ingesting a weird hippy chemical.

3. The faces and animals in your work seem both diverse and highly stylized. Where do the wide-eyed, snaggle-toothed casts of characters come from?

They are cute little things trying to have fun, be happy and find enlightenment just like the rest of us but smooth and shiny like living gummy brand products. The cast comes to me one by one. I can’t force it, I’ve tried. They insinuate themselves into my sketches. They come from a place in my head where nothing bad ever happens.

4. Explain what “surrational’ is and how you employ the concept in your art.

I don’t believe a person can approach a more direct dialog with the world than through presenting one’s own iconography and visual fetishes. My reoccurring characters and coincidences are meant to conjure an affect in the viewer with an application of what I refer to as “magical coincidence.” Magical Coincidence is surrational decision making. Surrationality is the pure instinct in the act of creating uncalculated or ironic surrealism. It defies common rationality. Traditional surrealism utilized juxtaposition of disparate elements. The surrational decisions in my work are made by intuitive thought: intuitions that may confuse me while pleasing my sense of drama. I first decided to utilize this method. After a dream I had in which various “Magical Coincidences” occurred. In this dream I found myself kneeling in a muddy field with my arms elbow deep in the wet soil pulling one strange artifact out of the ground after another. Each object was a natural occurrence of vegetable and root growth that formed impossibly close likenesses to rabbits, giraffes including a realistic and highly detailed bust of Abraham Lincoln as well. I peered up at one point and was confronted with an immense rabbit made entirely of various different colored jellies. When the sun shined through her body it made beautiful colored projections all over my arms. I don’t claim to understand these cryptic dreams, nor do I try, but I do recognize the elation I felt. When I accomplish this technique correctly I feel the same sensation: a blend of enlightened confusion and gleeful discovery.

5. When did you begin drawing?

My Mom kept a series of dismembered head collecting, ten story tall green skinned witches I did in kindergarten. The first memory I have is drawing one of those pieces in magic marker. I’ve spent a lot of my life drawing since then. I took a break somewhere around nine or ten to prepare myself for a life as a fantastically eccentric botanist. I still fantasize about being a botanist one day! I have enough cacti and succulents to keep me busy with plants though.

6. If you created an illustration of your life so far, what would it look like?

I like to believe that every drawing I do is the complete sum of all of my experiences up to the very moment my newest piece is finished. I like to think that maybe falling off my bike in the second grade is in the drawing somewhere near to a memory of a delicious slice of lemon meringue pie I ate last week. I can’t see it but sometimes I can feel it. I do know one thing for sure though; it’ll have bumble bees all over it!

7. What has been the biggest challenge or obstacle in your artistic career?

To get my creativity gland to work in tandem with my business gland.

8. Describe the ‘zine scene and your involvement in it. I moved to NYC in 1989 and landed an assistant job at Psychedelic Solution Gallery. I grabbed a cheap apartment (they were all cheap back then) and got to work on my portfolio. I drew every night until I couldn’t focus, on lunch breaks and on the subway to and from work. Before any paying clients opened their doors to me I got my chops together contributing to a multitude of ‘zines and independent art and music magazines like EXIT and Chemical Imbalance. It was a very exciting time for me. I was published with many well known figures like Robert Williams, Joe Coleman and Raymond Pettibon which was quite thrilling for a twenty one year old suburban kid. I was hooked.

9. What future projects are you working on?

I’m working on two children’s books, putting the finishing touches on my web site (happyhomeland.com), illustrating the texts of thirty eight authors for my next book, designing a series of ipod shells for MacSkinz, teaching adjunct at Syracuse University, recording drum tracks for a cd with my band “Atlantic Drone Quartet” and preparing a new series of drawings for my next show.

10. What is your personal definition of Art?

Great art looks like, acts like and smells like a prayer to me and bad art looks like, acts like and smells like a curse, that’s how I meter it anyway.

OLDER INTERVIEW with Steven Cerio (2001)

“Comfy Crater”

Steven Cerio interviewed by Jeff Mack (via email September 2001)

J.M. In another interview, you mentioned Francis Bacon, a painter who went to

great lengths to distinguish his practice from that of an illustrator. He

seemed to feel you had to distort a form in order to covey a feeling

accurately, that rendering an object too literally would be illustrating

and therefore unconvincing. Do you agree with this?

CERIO: In his time period, yes. Of course I’ve seen his work used as illustrations for anger and anxiety in the last ten years. There’s that pecking order-gallery artists look down on illustrators and illustrators look down on cartoonists. I can’t worry about that. I paint, illustrate, do animation and sculpt. It isn’t a sport no matter how they approach it; no one is going to win.

J.M. All of your forms are distorted yet there’s never an object that is

indecipherable. You seem always to return to a certain literalism. It’s an

interesting line to walk. Can you explain your desire to represent very

specific things?

CERIO: I’m in love with this world but I project enough sensations and delusions of my own on it. It doesn’t need me to step on it too much. I think that when you mess with everyday items you get Magritte-esque effect. He wasn’t surreal he was ironic at best. Putting things where they don’t belong isn’t surreal, it’s ironic. Ironies, or the sharp contrast of execution, are the staple crops of rock and roll and prime time television. That’s what passes as clever with suburban housewives.

Symbolism and alphabets are used as substitutes for experience. Words and symbols are shortcuts, not living experiences or creatures. There is no such thing as “mere things.” A chair used as a symbol is far more demanding than a halo. Which is to say it demands more from the viewer, creating more “experience?”

J.M. To what extent are you interested in making a reality?

CERIO: Well, I’m not a realist so that’s my game. I didn’t choose to, but that’s what art and music are right? Coltrane said “the main thing a musician would like to do is to give the listener a picture of the things he senses in the universe.” Everyone has their own homemade universe of common sense. I adjust things to fit the way I crave them. I want them soft, sugary and occasionally squeaky like dolphin skin.. I don’t approach my art as invention, it’s more like acknowledgement because I already know every molecule. But I’m always looking for a new strand of DNA.

J.M. Animals are an ever present theme in your work.

CERIO: Yeah, they’re more interesting than people…physically and mentally. You can understand the actions of your own species but I can’t figure out my cats. Animals have Zen and we make embarrassing attempts to mimic it People learn how to build cars and bees build honeycombs instinctually. I ‘ll draw a little girl now and then…but little boys kill frogs…little girls are harmless in comparison. Animals only harm when threatened or hungry except for one mammal aside from man and guess what species…gorillas, another primate suprise, suprise!! They will mangle acres of jungle out of boredom. I don’t think hedge hogs or sugar gliders make a habit out of that.

J.M. To what extent do to call your work fantasy?

CERIO: It’s just semantics but what the word ‘fantasy’ denotes to me is people daydreaming of a better world and life for themselves where they can enjoy complete control and admiration.That life usually incorporates spaceships, green women in skimpy bathing suits or swords. I’m not an escapist, not to that degree.

J.M. Do you feel there is ever a loss of integrity in terms of what your work means to you on a personal level if you have to make sure other people get it?

CERIO: An illustrator isn’t paid to have integrity. An illustrator is paid to sell an item, an article, or an idea for someone else. I think you compromise when you have an illustrative idea and ignore it because you are a color field painter. I think you compromise when you have an idea for a color field painting and you poo-poo it because you are an illustrator.

The tighter you fit into pigeon holes the better off you are. I wish I fit an established, comfy pigeonhole sometimes and had no other interests. Look at, say, Britney Spears. I may be wrong but I wouldn’t imagine that she cries herself to sleep at night because she never followed her dream to create the world’s largest popcorn sculpture. She fits the pop star mold to a “T”. I’ll never fit a pigeonhole like that…I say that with grief ‘cause boy that must be an easy ride. I believe people like that dream of their possible market and target group and lovingly dedicate all of their actions to it. I don’t believe they dream of reinventing any wheel so integrity plays no part in it. They just make sure that everyone understands them. They’re careful that soccer moms aren’t offended and middle aged moms won’t gasp when it leaks under their children’s door. Their aesthetic is so obvious and manipulative it frightens me. I’m horribly fascinated by pop culture. I have absolutely no understanding of it so I enjoy witnessing it. Lisa Frank notebooks, Hello Kitty clocks, shit…gimme more!

J.M. Your work looks strongly informed by the Surrealists, particularly Max

Ernst’s decalcomania paintings, Tanguy, Miro, and Dali’s Paranoid Critical

Method theories. Do any of these artists’ methods apply to you?

CERIO: The ‘joy’ in Miro’s work has always inspired me. Its lack of politics or comment is also inspirational; I feel the same way about Alexander Calder. The manifestos of surrealism affected me. Of course, I was already enjoying those freedoms and luxuries. They laid all of the track down before I was born. They taught me how to love my own phenomena and “you can only become enlightened by your own phenomena”like John Giorno said.

The first painting ever presented to me as a work by an artist and not a printed image was a Dali. My dad was a fan. Seeing as how I was 5 and it was the ‘summer of love’ it appealed to me immensely. I’d been bombarded with surreal images every day in the late sixties and early seventies. It was even on tv , I watched The Monkees’ and countless Fellini-esque French films on PBS with a bowl of Captain Crunch everyday. I began to believe…or know as the matter is, that understanding isn’t necessary for effect. Having to understand degrades experience. You can leave your decoder ring in your pocket.

J.M. Philip Guston called himself a night painter because he’d wake up the next

day and be surprised by what he’d painted the night before. I like that

idea of not being fully conscious of what you’re doing. How much of your

composition is automatic or improvised?

CERIO: I improvise 90% but the remaining 10% is composition, and that 10% is the spine and brain.

J.M. I would have thought most of it until I saw a sketch for a rabbit mobile

that suggested you might work with a predicted outcome. Is this rather the case?

CERIO: That sketch was for a mobile I knew I’d probably never get around to building. That’s why it’s far more realized than the thumbnail sketches that I actually work from which are usually composed of less than ten lines. Anyway, when I get around to that sculpture it’s needs will determine a hundred or so deviations from the sketch. I would never follow a sketch line for line. I don’t boss myself around. I don’t predict outcome. I only predict compostion, the rest is just frosting. If your composition is tight it doesn’t matter if your drawing thumbtacks, it’ll be appealing to great degree. Look at Franz Kline, it’s just black paint, right? It’s nonrepresentational and it still makes most realism look like little puddles of poopy.

J.M. You’ve mentioned to me an interest in Art Brut. What aspects of it apply to

your way of working?

CERIO: I give more attention to my hallucinations, daydreams, delusions and to anyone else’s art or music that hints at theirs. Art brut insinuates that everyone filters the world through their psyche, like staring through a transparency. That idea bashes the concept of mass marketing in the face. Sometimes I get sad wondering what I would draw like now, had I not studied at it for years. Skill doesn’t make the artist. It makes a better draftsman and craftsman. I prefer my next door neighbor to Rembrant. Henry Darger demonstrated American ingenuity in a room all by himself; while Norman Rockwell pimped himself off to grandmas.

J.M. Some of DuBuffet’s work with butterfly wings comes to mind when I look at

your images, particularly the complexity and obsessive patterning, secondary

images created by combining other images. However, he had the advantage of

using various materials, collage, pastes, mortars, etc. which could be

shifted around until they suggested something else. It would seem that

working with pen and ink, flat paint, or computer coloring these options are

out of the question. Is that true?

CERIO: I believe it’s just the opposite. I think it’s become easier to get those effects using new technology.

J.M. How much do your materials influence the way you work and the ideas you

arrive at?

CERIO: I arrived at my materials because of the ideas I’ve had. I got a “Jungle Book” Colorform for my birthday when I was 3…then my Mom gave me a viewmaster with a “Peanuts” reel. That got me thinking with my eyes. I came across that colorform in the Village a couple years ago…that’s when I realized the impact it had on me. Same palette I use, same color field logic and even similar line . The first drawings I remember doing were a series of giant witches walking through cities being attacked by U.F.O.s then I tried to mimic the line work from the mural in our shower. It was a water plant with shells and rocks.

J.M. You mentioned that you hope to communicate a feeling of joy. Is this still

important?

CERIO: Yes. That’s all I care about really. Misery and discontentment are easy to come by. Happiness takes work. Nothing good comes easy. Joy can only be found through action. If you sit still and never seek, you starve and die. Stagnate and you create nothing. You have to move through as much space as possible and pick up molecules to help you along the way. Work sets you free. This universe makes it difficult to live in pure bliss, why?. Sadness is always present and happiness is always fleeting. Why isn’t the state of the universe a vast milkshake of smiling creatures and positive, immortal occurrences? That’s why I dedicate myself to it. I get up inside it sometimes. Every time it lets me stay a little longer. I’ll trap it one day and feed it mallow cups and gumballs, walk it around on a leash like in that Zen narrative painting of the water buffalo and the farmer boy .The first panels the buffalo does as it wants, completely oblivious to the boy. By the end, the buffalo: which is meant to represent the id, follows him like a dog. I think adults generally equate sadness, violence, irony and misery with maturity while they equate joy and bliss with immaturity. I’m not cool enough to be bemused I guess. I’m very excitable.

J.M. If you conveyed a different emotion would it be a failure?

CERIO: I’ve tried to communicate sadness but the pieces seem to be sarcastic and mocking which is nice. I’ve been working on a series of them on and off for the last few years.

J.M. To me, there is also a menacing quality about your pictures. They suggest a

mind out of control, or a hallucinatory state. It’s something that’s often

seen as recreation today (probably more so in the 60s and 70s) but can

easily become a terrifying situation.

CERIO: Menacing? Adults find my work menacing and children think it’s silly. It’s that phenomena I just mentioned. My smiling animals are menacing, but a Giger painting is “cool.”

As far as hallucinatory art goes, I’d look at nothing else. I’ll draw nothing else. I create my images because I wish they’d happen. I honestly have no idea why someone would draw a realist still life. I’ve experienced apples and a wood bowl before. The invention of the camera should have put an end to that sort of imagery.

Terrifying situations? If you hang out with misery, frowns and that boring anxiety in your head, hallucinogenics are going to bring that out and it’s going to make you stare it all in the eye. Your brain isn’t out to get you; it’s just inviting your friends to dinner.

J.M. You have an entire alphabet book about them, so do you predict your audience

will be using them?

CERIO: People have craved alternate states of consciousness since the beginning of time and have certainly developed the tools to achieve it: cigarettes and alcohol included.Aldous Huxley called it “artificial paradise.” My drug book is about all drugs, not just hallucinogens. Most people made the mistake of thinking those were my personal feelings on those drugs. One reviewer said I acted kindly towards my favorites. That’s silly! I was using the general public’s views and stereotypes about those substances and illustrating them. Now, speed for instance invokes no heartwarming or silly stories while marijuana has no dark stigmas attached so I could approach the two very differently. Another way I metered stigmas was considering which drugs people will admit to consuming. No one will pull out their works and shoot heroin in mixed company, or admit they did a line in the bathroom, so it’s safe to say the culture holds taboos about various substances.

J.M. Have you ever spoken to someone who’s looked at your work in a

hallucinatory state? What was their reaction?

CERIO: I’ve heard from people who’ve blown up various drawings of mine for their black light rooms or collected my black light posters and told me about how well they work on them under the influence of various substances. Someone recently approached me to print my work on blotter.

J.M. One of my strong memories of childhood was how much psychedelia entered

mainstream popular culture in shows for kids like Sesame Street and Alphabet

Soup. People were stretched like rubber bands and turned into clocks and

fountains or disappeared into thin air. The physical world was impermanent

to an exaggerated degree. Why do you think children’s entertainment and

drug culture have so much in common?

CERIO: Those were liberties that you couldn’t take with entertainment till the summer of love. 50’s culture would never allow that. They were selling coiffures and germ free well being. Aside from the beats the 50’s were about ‘how do we get there, where’s the map’ the 60’s were ‘let’s go!’ It was about the ride. I think what children’s entertainment has in common with drug culture is that children want their entertainment to be elevated from every day life. I think that the pivotal point of the cross pollination of the two was Syd and Marty Krofts shows,”Lidsville”, and “H.R. Puffinstuff”. They are not hiding the drug references there eh? Seuss was another cross pollinator albeit innocently and unintentionally. Now, Seuss…Shit, what a genius in every conceivable way.

J.M. Animation seems like such a perfect medium for synthesizing alternate states

of reality. It’s too bad it’s so often used to solidify just the obvious

one. Have you ever worked with animation?

CERIO: I have “Happy Birthday” cakes, presents, candles and other stuff on Nickelodeon Jr. every morning. The characters come out and sing happy birthday to whatever children may have their birthday that particular day. It’s been running for 6 or 7 years now. I’ve also done two pieces with The Residents. I created the shooting targets for “Dixie’s Kill a Commie Shooting Gallery” for the “Bad Day at the Midway” cd-rom Jim Ludtke did such a beautiful job animating and it doesn’t hurt having a Residents tune playing along with it either. My section was just re-released on their new “Icky Flix” DVD along with a film I did with them for prime time German television called “Disfigured Night.” John Payson directed that one. The Residents projected various images via computer to backdrops behind a live performance, Payson filmed it then edited in more animations. It’ll be out on DVD in early 2003 the last I heard.

J.M. Have you seen Bruce Bickford’s work?

CERIO: What kind of Zappa fan would I be if I didn’t witness the work of “The Amazing Mister Bickford?.” I can’t even imagine the time frame on his projects. They seem mostly improvised as well which makes them even more impressive. I love that you can see finger indentations moving all over the plasticine while the action moves. His interview in the “Baby Snakes” film is as trippy as his animation.

J.M. One thing that concerns me about making a living as an artist is the need to